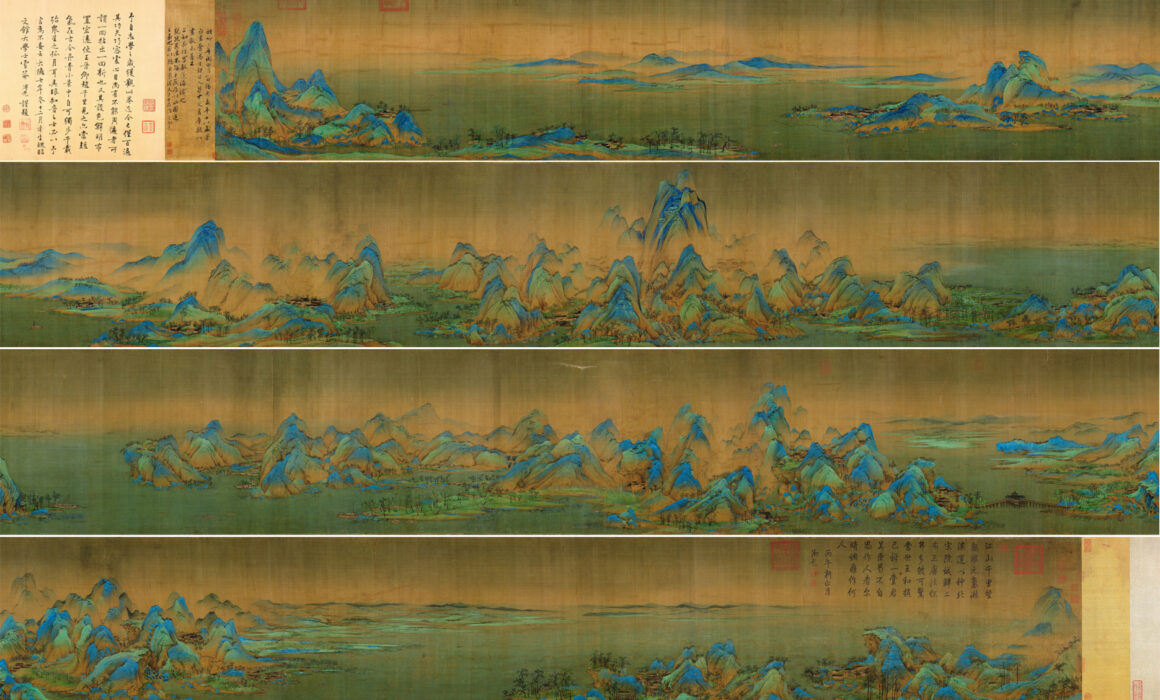

Mountain and Water Painting as a Tale

Issue 1 – Author: Giacomo Bruni

Italo Calvino Hypothesis of description of a landscape

Whenever I have tried to describe a landscape, the method to be followed in the description becomes just as important as the described landscape: I start by conceptualizing that the operation is simple, delimiting a piece of space and describing everything I see in it; but here I have to decide if I want to portray what I see from a standing point of view, as painters usually stand, or at least they used to at the time when painters painted landscapes from real – time which lasted three centuries to say the least, a phase very short in the history of painting – or to portray it moving from one point to another within the piece of space so that I can say what I see from different perspectives. Multiplying the points of view within a three-dimensional space. This second system presents itself as the most correct when it comes to a rather large space, where the eyes cannot embrace its surroundings in a single glance; just as how the act of writing is an act of movement in itself. Like how when I’m sitting here writing, I may seem still, but it’s the eyes that move, the outer eyes run back and forth following the line of letters that runs from one edge of the sheet to the other, and the inner eyes also run back and forth between the scattered things of memory, and they try to give it a sequence, to draw a line between the discontinuous points that memory keeps isolated, torn from the true experience of space; I have to reconstruct a continuity that has been erased from my memory with the footprint of my steps or the wheels that led me along paths that was once taken hundreds of times. So, it is natural that a written description is an operation that stretches space over time. Unlike a painting, or even more than a photograph, which concentrates time in a fraction of a second until it disappears as if space could exist on its own and enough for itself. But I must say that while I scroll through the landscape to describe it from different points of its space, I am also scrolling through the different moments in time when I was in motion. Therefore, a description of a landscape, being charged with temporality, is always a story: there is an ego in movement, and each element of the landscape is charged with its temporality, which is, with the possibility of being described in another present or future moment.

Italo Calvino