Mountain and Water Painting as a Tale

Issue 1 – Author: Giacomo Bruni

Italo Calvino Hypothesis of description of a landscape

Whenever I have tried to describe a landscape, the method to be followed in the description becomes just as important as the described landscape: I start by conceptualizing that the operation is simple, delimiting a piece of space and describing everything I see in it; but here I have to decide if I want to portray what I see from a standing point of view, as painters usually stand, or at least they used to at the time when painters painted landscapes from real – time which lasted three centuries to say the least, a phase very short in the history of painting – or to portray it moving from one point to another within the piece of space so that I can say what I see from different perspectives. Multiplying the points of view within a three-dimensional space. This second system presents itself as the most correct when it comes to a rather large space, where the eyes cannot embrace its surroundings in a single glance; just as how the act of writing is an act of movement in itself. Like how when I’m sitting here writing, I may seem still, but it’s the eyes that move, the outer eyes run back and forth following the line of letters that runs from one edge of the sheet to the other, and the inner eyes also run back and forth between the scattered things of memory, and they try to give it a sequence, to draw a line between the discontinuous points that memory keeps isolated, torn from the true experience of space; I have to reconstruct a continuity that has been erased from my memory with the footprint of my steps or the wheels that led me along paths that was once taken hundreds of times. So, it is natural that a written description is an operation that stretches space over time. Unlike a painting, or even more than a photograph, which concentrates time in a fraction of a second until it disappears as if space could exist on its own and enough for itself. But I must say that while I scroll through the landscape to describe it from different points of its space, I am also scrolling through the different moments in time when I was in motion. Therefore, a description of a landscape, being charged with temporality, is always a story: there is an ego in movement, and each element of the landscape is charged with its temporality, which is, with the possibility of being described in another present or future moment.

Italo Calvino

This text by Italo Calvino entitled Hypothesis of description of a landscape that introduces the volume Esplorazioni sulla via Emilia (1986), is full of ideas for our considerations on the differences between landscape painting and of mountain and water painting; two forms of art that despite having nature as its subject, have two profoundly different forms of expressions and purpose. In the brief text, we’ve read how in the representation of the landscape in figurative arts such as painting and photography, creates static works, which describes the landscape as capturing it in its instantaneousness. Since they are limited by a unique and mono focal perspective, it cancels time, leaving space as the only expressive element. This applies to the artist, who with his work deletes the passing of time, and this equally applies to the observer who in a single glance manages to embrace the whole subject, the entire scenery. This is due to the fact that the Western painter by choice and by regards to photography by condition, bends his expressiveness to the laws of optics. As Simmel observes in his fundamental observations on the landscape, a portion of nature is not yet a landscape. An act of the observer is needed which, by looking at it, absorbs the matter and recreates or recomposes it in itself, thus creating the landscape. But this process always develops according to the laws of optics, which is how westerns perceive and express the material world, at least from the beginning of modernity onwards. When we talk about the laws of optics we refer mainly to the focal or Albertian’s perspective and not so much to the naturalistic representation of the subject. The landscape painters of western modernity voluntarily sought visually real effects, in a period when photography was still taking its first steps; but also looking at contemporary landscape painting we see how the artist has moved away from the mimetic representation of nature, yet it is still difficult to separate it from the slavery of the mono focal perspective, this is probably because it does not detach itself from the anthropocentric vision of the world and the artist “ego” and perhaps because it does not think about the possibility of other methodologies to relate to its surroundings.

Instead, writing, as Calvino explains to us, is an operation that develops in space and time. Since the writer is analyzing the landscape from different points of view, moving in space and time, the description of a landscape is full of temporality and this always makes it appear like a story. This idea is also applicable when describing mountain and water paintings, whose realization methods follow those described by Calvino for writing. And this is one of the main factors that differentiates it from landscape painting.

The artist who approaches mountain and water painting does not see the natural environment as a landscape, like a view or a fragment of nature included in the optical cylinder, but relates to it as an environment and not an area limited by sight. The portion of nature that he chooses as his subject, he will then walk and observe it, from near and far. As Guo Xi 郭熙 (1020-1090), a famous painter and theorist of the Song dynasty tells us, the mountains do not have a single shape, but are a set of infinite shapes, which cannot be understood or captured in a single glance. This entails the need to collect different perspectives of the subject of the painting, immersing ourselves in the environment in order to understand its details, proceeding to discover new hidden elements and then observing it from afar to better understand its general structure, in order to be able to fully understand the mountains, rocks, trees, streams, waterfalls and everything that characterizes the natural environment that we want to translate into the painting.

In reproducing this natural complexity, the painter will have to proceed in a manner explained by Calvino to describe the landscape, therefore following his reasoning, the painting of mountain and water is always like a story. The observation of such a work is a tale and also a dynamic experience, precisely because of the formal characteristics of the painting. The observer is led to travel in it. Since the unifocal perspective is an inadequate mean of expressing the artist’s needs, the artist will have to rely on perspective multiplication and this condition makes it impossible for the observer to embrace the painting in a single glance, but would have to travel in it just as the painter did in assimilation phases of the natural environment. This is precisely one of the main objectives of Chinese painters since ancient times. Zong Bing 宗炳 (375-443) wrote one of the oldest texts we have concerning mountain and water painting. In the final section of the Introduction to painting of mountain and water, (Hua shanshui xu, 《画山水序》) he writes:

“In moments of relaxation, after having put my mind in order, emptied a glass of wine or strummed the lute, I unroll a painting and sit in front of it and without leaving the crowded houses of men I find myself wandering in solitude, in wildlands, with no trace of human beings. Mountain peaks rise above the clouds, gorges and forests extend into the distance. The wise and virtuous shine from antiquity, and all the interesting aspects of life come together in the mind. What else do I need? Being in this state I am happy and delighted, what more can I ask for?”

于是闲居理气,拂觞鸣琴,披图幽对,坐究四荒,不违天励之藂,独应无人之野。峰岫峣嶷,云林森眇。圣贤暎于绝代,万趣融其神思。余复何为哉,畅神而已。神之所畅,熟有先焉。

In these lines we see how appreciating a painting is a process similar to that of reading a book, as in a story, we find ourselves wandering in unknown lands and meeting fantastic characters. In addition to receiving the visual pleasure of the natural beauty in front of us, the painting alienates us from the chaotic reality in which we live in, delighting us but also reinvigorating us spiritually. So, when we look at a painting the eyes naturally follow the paths between the mountains, which can lead us to high peaks with hidden temples and pagodas, or go up a waterfall which enables us to discover a hidden and unspoiled valley. The course of a river may lead us to distant forests that disperse in the fog, whose emptiness carries the eye towards dizzying peaks that rise in the distance. These are just some examples of the experiences we can live by observing a painting, experiences that can coexist in the same work.

We have read how Zong Bing unrolled the painting, this is because Chinese painting of any kind is made with ink on paper, so that the works can be easily rolled up and stored. Traditionally the works were not exhibited, but unrolled and observed when required by the occasion. This type of execution and use of the work has also influenced its formats, where as in addition to the more common ones such as vertical, horizontal, square and circular, there are other more particular ones, for example the long scroll, called changjuan 长卷, which usually has a height of about thirty centimeters, which can be extended to a length of several meters. This format for obvious reasons, is difficult to expose. The methodology for observing the work is to unroll it and re-roll it from right to left, causing the mountains and rivers to flow in front of our eyes. In this way, the portions of the work fade as they glide in front of us, as if we were leafing through a book, like a story, the subjects are placed in such a way as to make observations dynamic. Exciting scenes of dizzying heights, rocks of all shapes and sizes or ancient lumpy pine trees will alternate calm waters, reeds caressed by the wind or find a solitary traveler who walks among bamboo groves. In the contemporary world, in galleries and museums for obvious conservation reasons, it would be impossible to unroll and roll up the works at will, therefore these long paintings are placed on tables in all their length. Even in this situation it will be impossible to observe the painting with a single glance, but the observer will have to walk along its entire length. In this way movement is created in observing the work, as if a story was flowing before our eyes. In this regard, another interesting text is by a famous painter of antiquity, Gu Kaizhi 顾恺之 (346-407), whom in his notes on the painting Hua yun taishan ji《画云台山记》describes how he proceeds in the realization of such a painting. Its indications concern a whole series of instructions on how to position the mountains, clouds, waters, roads, animals, a master and his disciples, mythological creatures, lights and shadows, creating a sort of tale full of details and vitality.

Additional characteristics that unites the observation of mountain and water paintings to reading of a story is, as previously declared, the illusion of escaping reality. In fact, Zong Bing tells us that despite being in a crowded city, he finds himself wandering among lonely lands. This is one of the goals that this kind of painting aims to achieve. Guo Xi wrote a famous text on mountain and water painting, (Linquan gaozhi 《林泉高致》) he writes:

“It is in human nature to feel the hustle and bustle of society and desire to see spirits and immortals hidden in the clouds. In times of peace, under a good emperor and excellent parents, it would be wrong to leave to be alone, because there are duties and responsibilities that cannot be ignored […]. The dream to retreat in the forests and springs and to find oneself in the company of clouds and mists is always there, but the eye and ear are deprived of it. Now a good hand has reproduced them for us. Without leaving your room you can imagine yourself sitting on the rocks in a gorge and listening to the screaming of monkeys and birdsongs; while the light of the mountains and the colours of the water dazzle the eyes. Isn’t it a joy, a realization of a person’s dream? That’s why mountain and water paintings are so in demand. Approaching these paintings without the necessary mood would mean ruining this magnificent view and clouding the refreshing breeze.”

Once again, we see how the effect produced by observing the painting is the same as that produced by reading a tale, in which it takes us to fantastic places and invigorates our soul without having to set foot outside our room.

Thus, although the mountain and water painter use sight as means of knowledge of the natural environment, he will not bow to the laws of optics in his expression. Similarly, as the writer who in describing a subject will not just list its characteristics, but instead will rework them so as to involve the reader, the painter will create a work that will make the observer immerse himself, in which the painting will no longer be an external element, but he will feel inside the painting, free to travel according to his will, healing that fracture, cancelling that space that creates the unifocal perspectives.

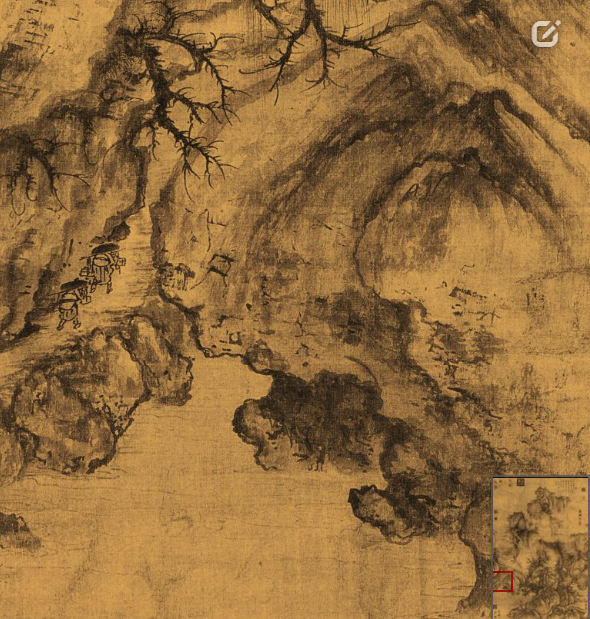

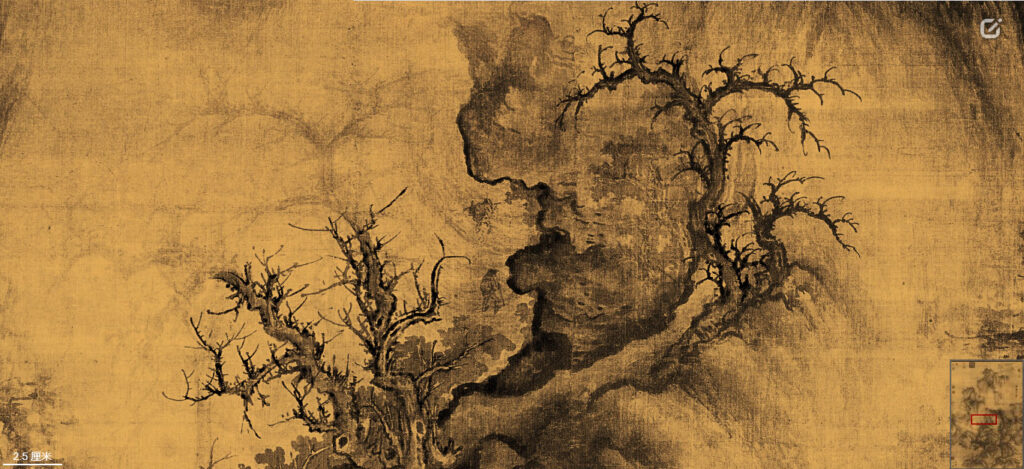

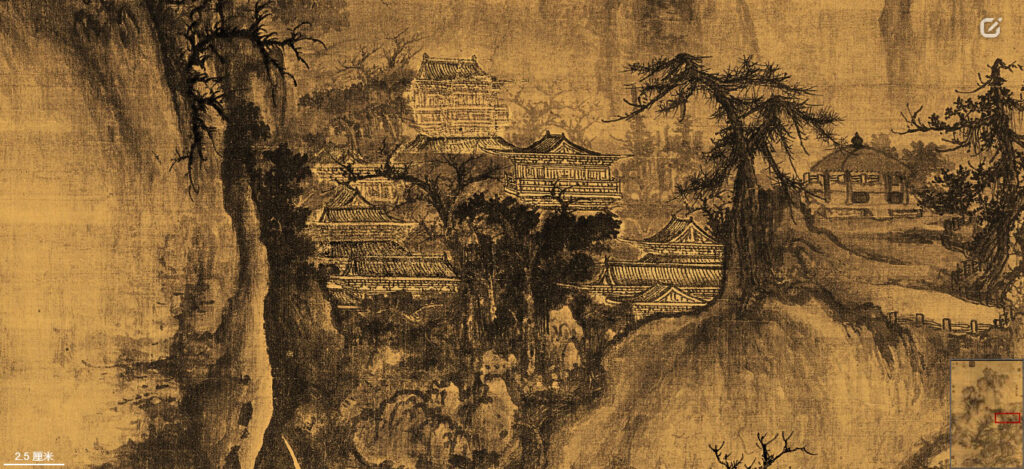

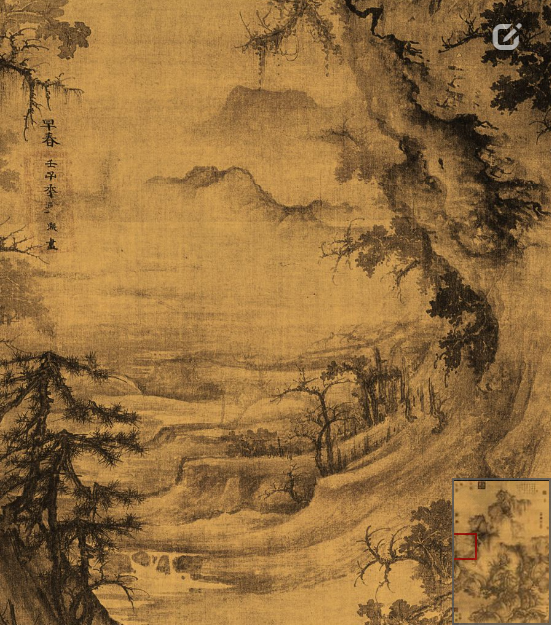

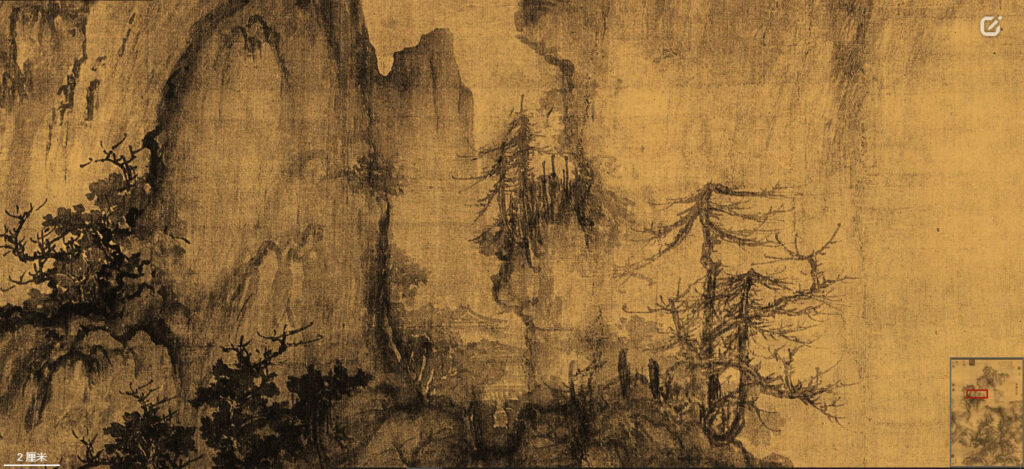

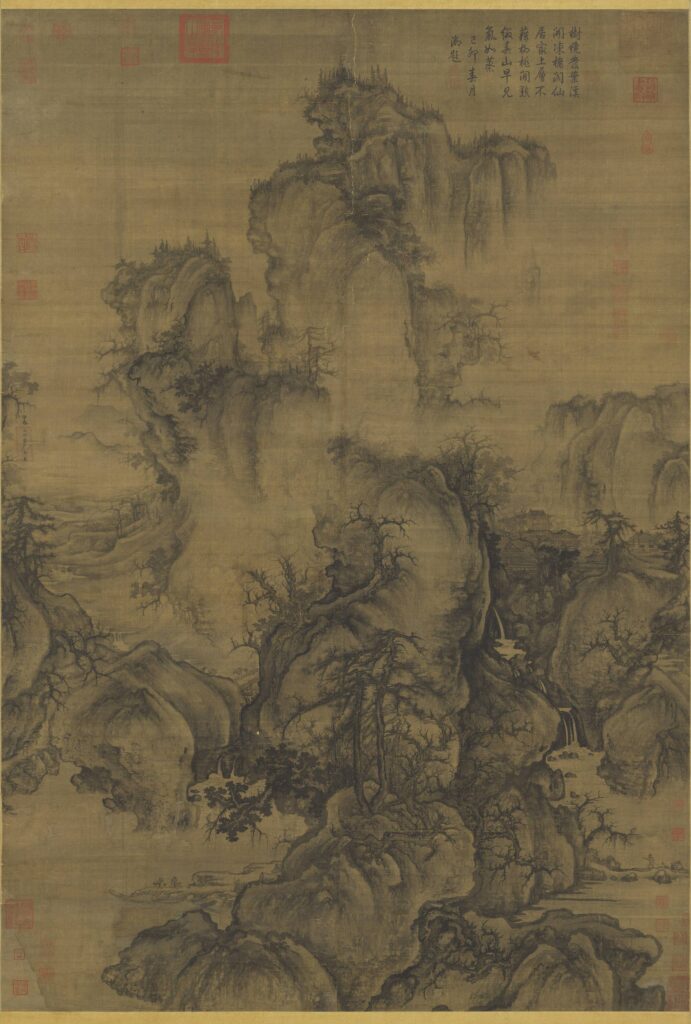

As an example, let’s take Early Spring《早春图》 (158.3 x 108.1 cm) of Guoxi, painted in 1072. It is one of the most famous paintings of the Song dynasty and in the history of Chinese art, which is currently a part of the collection at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. In this work we clearly see the effectiveness of using multiple perspectives which describes the various portions of the mountains, and not just the front ones suggesting the extension of the mountain beyond the visible. A closer perspective shows us the trees and rocks that are at the base, surrounded by flowing waters brought to the valley through numerous waterfalls coming from the highest areas of the mountains or from valleys that extend in the distance. Similarly, through a higher perspective, the various peaks appear clear to us with their vegetation that merge into the mists. The skill of the painter succeeds through a play of empty and full spaces to give movement to the work and by giving vitality to all the portions of the various rocky masses that form the mountains. The voids of the work which represent the mists, have the role of giving impetus and agility to the massive forms and suggesting the extension of the natural environment that is in front of our eyes. This dialogue creates the movement that will guide the eye within the work, enabling it to wander through the mountains, valleys, waters and forests. Our wandering will not be accidental, the structure of the work is such as to guide us to different places. The rocks below attract the first glance as if they were a gateway to the mountain area described in the work. From there, through various roads we can undertake different itineraries that lead us to discover a whole series of elements that are difficult to notice at a superficial glance. These elements can tell us different stories or let us discover “unexplored” areas found in the work.

So, if we start our ascent from the masses of rock and earth to the right, soon we encounter a couple of fishermen, where one of them intents on bringing the boat back to the coast, while the other checks or replaces the fishing nets. Behind them is a waterfall visible from in-between two large rocks.

The vertical course of the waters brings our gaze to rise rapidly to the highest peaks. If, on the other hand, our attention is drawn to the water to the left of the painting, we come across a family of four: a mother with a son on her lap, a father, another son and a companion animal that precedes them. The family is returning from a boat trip, loaded with luggage, which in all probability heads towards the house surrounded by a reed play that hides amongst the nearby rocks.

Continuing to observe the water area on the left, we notice two travellers walking along a road that runs alongside the mountain and overlooks the stretch of water at the left edge of the work. The two travellers wear large headdresses to protect themselves from the sun and are loaded with luggage. Despite being small figures, we can guess their effort in climbing the path.

The road is hidden by the rocks, but mentally following its path, we are able to find it back. This road leads to a bridge that crosses a distant river and at that point turns into a waterfall. There are three figures crossing the bridge, a wealthy character with a large hat riding a horse, preceded by two walking servants carrying his luggage.

The road continues and disappears between rocks and vegetation, but a little further on we find it back escalating up the mountain, where there are two other characters, one with a hat and a walking stick preceded by another figure who is probably a servant. The servant has his head uncovered, bent by the weight of the carrying a pole on his shoulder and certainly tired from the steep climb.

The path that continues to go up disappears from our sight behind a rocky wall where the top is covered by trees and plants that disappear in the depth and merge into the mists. Even if the road no longer appears before our eyes, we can assume that it leads to the temple complex that is located to the right of the work. A series of finely painted buildings develops in a gorge surrounded by rocks and vegetation, on one side they overlook waterfalls and its waters reach the fishermen’s boat. In all likelihood, this is the goal destination of the seven characters we met along the path, a path that also indicates a spiritual path, both for the figures in the painting and for the observer, who precisely has the temple as a goal. To the right of the sacred building, there is a pavilion (tingzi亭子) on top of a hill, a building dedicated to leisure time, where it is possible to sit and admire the beauty of the nature, play chess, read a book alone or in company etc. Here we notice two empty benches, and right in front of the benches there is a natural fenced terrace, or what we now call belvedere, from where is possible to admire a landscape that we are not given to know, in fact the observer of the work it is located on the level where the landscape would extend, which opens up to the view of those who hypothetically overlook the belvedere.

This is one of the elements that manage to project the natural environment outside the painting, extending its borders out of the visible. The same thing happens in different areas of the work, we see how a valley extends behind the temple which is hidden by rocky walls and mists, that guides our eye or towards the top of the main mountain and its sheer walls, or towards the void that frees the gaze and lets it rest on other places of the painting. But if we go back to the bridge where the traveller with the two servants are, our eye could be attracted by the waters that flow under the bridge and go up the river current, which after a series of small waterfalls, takes us to a valley that develops to the left of the work, which reveals distant mountains, trees and mists that extend in the distance and behind the mountain that occupies the central part of the work. The valley takes us away from the main subject of the work and makes us imagine areas that are outside the plane of painting, as if it were a way out of the painting.

If we de-contextualize this portion from the rest of the painting, this can be a work on its own, with its waters, forests, rocks, mountains and mists. Thus, moving away from the main subject, we can return to it through new ways, which are not visually expressed but which can be intuited through the observation of other elements. The area to the right of the valley is covered by a spur of rock that belongs to the main mountain, and afterwards we see another rocky wall that takes us almost to the top, but between the wall and the spur we can see a gorge with a mountain in the distance which seems to belong to the valley on the left, as if there is a road that goes up from the rear area of the mountain to the gorge that is in front of us. If we carefully observe the base of the gorge, we will see another temple appearing among the vegetation, which seems unreachable from the side of the mountain that appears in front our eyes, since there are only sheer walls and sheer rocks.

Through this analysis we notice how in the painting there are several stories in progress, taken in medias res, where the characters’ actions are in progress and we can imagine where they come from and where they will lead. We also see how the layers of the painting extend outside it, the masses of rocks and soil and the large pine trees at the bottom are the elements closest to the observer, a sort of entrance to the work, which after long wandering can take us to the belvedere terrace which opens up to a 180 degree view which is not revealed to us by the painter, leading us to imagine high mountains or plains, or it can take us outside the painting environment to see ourselves in the act of appreciation of the work. Other routes can lead us to plans that extend into the distance, from which we enter through valleys, gorges or from the voids created by the mists that rise during the early spring.

This is just an example, it is possible to make the same kind of analysis for all the other mountain and water paintings, from the past and from contemporary times. The structure of the painting will guide us to discover its hidden places, to travel around the mountains and gorges, with the possibility of running into different kinds of characters, from the reality or characters fantasized by the painter. These could be historical or mythological figures or common people as well. Like a novel that could tell us all kinds of stories, through different kinds of characters and situations, the painter has just to follow his will to make it a more or less narrative work. And to understand this, the observer will have to let the painting guide him through its secrets and hidden places. For this reason, when we approach a mountain and water painting, just as approaching a book, in order to fully experience the piece of art, we have to spend some time with it. It won’t merely be enough to give a quick look or a gaze, it is not a kind of art that could be appreciated in its instantaneousness, but would require time and involvement.

Look at the painting in high definition

Read the article from the magazine, download it from here

Author: Giacomo Bruni