Why mountain and water painting

Issue 1 – Author: Giacomo Bruni

Why do we say “mountain and water painting” and not how it would be customary to say, “landscape painting”? Mountain and water painting is the literal translation of the Chinese denomination Shanshui hua 山水画, therefore the field of our artistic productions and observations that are going to be made will belong to the sphere of Chinese painting. But this is not the only reason, nor is it the most important one.

The main motive lies in the actual meaning of the term landscape. If we look at European languages, the term “landscape” is relatively recent (XV-XVI century), and always refers to a portion of land. Land- in Germanics languages and pays– and its variations in the Romance languages and in various other Slavic languages. The portion of land is what is contemplated by the artist or by a viewer in general, so it is limited by the sense of sight. Contemplation presupposes the gaze that goes from the observer to the subject in front of him, an act that inevitably is static and limiting. This is even more true when the landscape is represented in visual arts. In this area, western painting and photography bends to the laws of sight and to a focal perspective, presenting a view of a portion of the land which can even be 360 degrees but it still remains a view. In this case, the landscape work of art can be completely embraced in an instant with a single glance, not because of the size of the work, but because of its structure. For this reason, it is static as it cancels time and movement. Another effect that it produces is extraneousness. The work reproducing the visual perception of the artist automatically places him outside the scene, and the same applies to those who look at it.

Staticity, estrangement and submission to visual laws are three aspects that come into serious conflict with Chinese landscape painting. Shanshui hua means mountain (shan) and water (shui) painting (hua), a name that defines the favourite subjects of this pictorial category. The name alone shows an aspect of movement: the duality between mountains – static and massive elements – and the waters – everflowing and ever changing – well expresses the archetype Yin and Yang, namely the opposites that do not enter in conflict, but need each other to give full expressions of themselves. Furthermore, the generality of the term breaks down spatial boundaries, those boundaries that recall the terms land– or pays-.

In Mountain and water painting, the focal perspective is seen as an expressive limit. The viewer must not feel stuck in a portion of the landscape, nor outside of it. It must portray the feeling of being able to move freely inside of it and also feel surrounded by it.

These assumptions, while giving life to different works, which naturally produce different sensations from the western ones, lead the artist to deal with the subject and with the production of the work in different ways. The most eloquent example is the fact that the painting process of mountain and water does not include painting en plein air.

In Europe, en plein air painting was introduced by the Barbizon school and then taken up by the impressionist landscape painters or by painters such as De Nittis who painted in a carriage that was transformed into a mobile atelier. These artists hoped to make their works as “real” as possible, as if they were in a silent challenge against the new-born photography. In fact, the Barbizon school is a landscape current of realism and the impressionist landscape painters, most notably Monet, were fascinated by the luminous variations. Light is the fundamental means that makes visual perception possible. Western Renaissance and modern paintings that are basically mimetic, give to light a major part which shows just how much in Western thought, the perception of reality is tied to the perception of the vision. In pictorial sense this is a key factor that has influenced and continues to influence artistic productions. In fact, it is very difficult for a Westerner to detach himself from the axiom/yoke of sight.

Unlike in the Chinese context, en plein air painting is considered limiting, precisely because it binds the artist to the visual perception of the environment he wants to recreate, which in turn produces all those problems mentioned before. Explanatory is a passage from an essay on the painting of mountain and water by a great painter of the Song dynasty will perfectly summarize this concept. Guo Xi lived during the eleventh century, and in his Linquan gaozhi 《林泉高致》 writes:

A mountain seen up close has one aspect, and it has another a few miles away, and yet another one from further away. Its shape changes with each step. The front view of a mountain has one view, another view from the side and another from behind. Its appearance changes from every angle, as many times as it does the point of view. So, it is necessary to realize that a mountain combines in itself several thousand shapes.

山近看如此,远数里看又如此,远十数里看又如此,每远每异,所谓山形步步移也。山正面如此。侧面又如此,背面又如此,每看每异,所谓山形面面看也。如此是一山而兼数十百山之形状,可得不悉乎?

Reading this passage, it is evident that en plein air painting, and the Albertian perspective is not a suitable means to represent mountains or nature in general, and as a unifocal gaze is totally inadequate. Therefore, to represent a complex subject such as the mountain, first of all, a process of study and assimilation of the subject is necessary, and only then will it be possible to represent it through a painting. Another implicit aspect in these lines is that this painting will not consider only a portion of the territory, but it will attempt to express the totality of the subject, precisely through the use of different perspectives. Sight is a means of knowledge of the subject and one of the rules to be followed in the representation, but not the only one. The skill of the painter lies in being able to harmonize different points of view and different perspectives in a single work, making it harmonious and natural in the eyes of the observer.

In order to be able to express the richness and variety of his subject, the artist needs a deep knowledge of it, which it will not be possible to acquire through a single point of view, but needs a more complex and profound relationship with the environment and nature. For this reason, many of the greatest mountain and water painters in Chinese history embraced a life outside the cities and from the centers of political activity, to move to the solitude of the mountains and live in close contact with the subject of their art. In any case, the visual experience is an important aspect for the artist in order to represent his subject.

The obstacles when visually approaching the natural environment is a problem that has been treated since the time of the first theoretical texts on mountain and water painting. The first systematic theoretical text Introduction to Painting of mountain and water 《画山水序》 by Zong Bing 宗炳 dates back to the first part of the fifth century. In this early treatise we can already see how only relying on sight to perceive and depict mountains and waters is a limitation, a partial understanding. The primary problems dealt with were the proportions of the various subjects and the possibility of representing vast distances on small surfaces such as those of pictorial support. The reflection on proportions is very important, in fact in texts related to painting we do not find statements like “what is close is large and what is far away is small, in proportions of its distance from the observer”, a rule that is at the base of the unifocal perspective. There are statements like those of Wang Wei 王维 in the treatise On mountains and waters 《山水论》,that stand out. In one passage he states: “a mountain measures a zhang, a tree a chi, a horse a cun, a man a fen”, “丈山尺树,寸马分人” , therefore by physical measurements (expressed in different measure units) are applied in painting. Afterwards he proceeds to give practical indications on how to paint distant subjects: “distant men have no eyes, distant trees have no branches, distant mountains have no stones, so they should be painted like indistinctive eyebrows; the water in the distance cannot see waves, so they should be connected with the clouds and sky “,” 远人无目,远树无枝,远山无石,隐隐如眉;远水无波,高与天齐 “. In these passages we see how the author never talks about the change in size and proportions of what was being observed, because a tree near or far, in reality always has the same height, its shrinking is an illusion. The difference in size of the subjects within the work is only partially related to the proximity or distance factor, there are other factors that compete for it. These other factors follow the expressive needs of the artist, which elements he wants to give relevance to and which less, and how these elements relate to each other within the painting, between main and secondary subjects, following the natural relations between them. The differences in size of the various subjects are not in relation to the observer or the painter of the scene, but are in relation to each other, Guo Xi writes: “a mountain that rises in its size becomes the master of the other peaks developed around it, it becomes the centre of attraction of the elements that surround it. Whether large or small, distant or close, like a king receiving homage from his courtiers “,”大山堂堂为众山之主,所以分布以次冈阜林蟹,为远近大小之宗主也。其象若大君 赫然当阳,而百辟奔走朝会,无僵塞背却之势也 。” It is the same concept expressed in a more concise way by Wang Wei: “First, the orientation and height of the main mountain must be determined, then follow the peaks that surround it “, “定宾主之朝揖,列群峰之威仪”.

During the Song dynasty, perspective techniques were standardized, which lead to the general descriptions of the expressive possibilities of the artist in approaching mountain and water painting, and formalizing the scattered perspective system. The first to do so was Guo Xi, with his three distances rule: the high distance rule (gaoyuan 高远), observes and reproduces the subject as if it was looked at in all its height, from top to bottom and from bottom to the top, used in particular to represent large mountainous bodies in order to express all their grandeur and magnificence.

The second is the deep distance rule (shenyuan 深远), that is, to describe the depth ‘of the environment, therefore valleys, rivers, or other natural elements that develop in depth, which moves away from the observer.

The third is the level distance (pingyuan 平远), which describes landscapes in the distance, with mountains that develop more horizontally than vertically, often characterized by large empty spaces that increase the feeling of distance and the vastness of spaces.

Subsequently to Guo Xi, three other distances were added by another artist called Han Zhou 韩拙 (twelfth century), his perspective rules have a more atmospheric characterization than those from Guo Xi. The first is called broad distance (kuoyuan 阔远) which is characterized by large expanses of water that separate the observer from the mountains that rise in the distance, in this case increasing the feeling of emptiness and the perception of large spaces.

The second is called shrouded distance (miyuan 迷远), where mist and fog almost hide the landscape, creating a feeling of mystery and quiet.

The final one is remote distance (youyuan 幽远), which indicates those natural elements that are located at a great distance, creating a scenario that the observer cannot reach.

In addition to the formalization of the six distances, which had a lot of influence in the generations of successive painters, it is possible to find in theoretical or poetic texts, or through the observation of the paintings, other methodologies of visual approach by artists towards the subject to represent. In two poetic texts by Su Dongpo 苏东坡 (1037-1101) a dynamic and non-static approach is proposed in the observation of the natural environment. The first two verses of the poem On the walls of Xilin 《题西林壁》 quote: “looking from the side, a mountain range appears, in front you can see the peaks; highs, lows, near, distant, all are different “,”横看成岭侧成峰,远近 高低各不同”, he refers to the fact that for each point of view the scenery of Mount Lu 庐山 changes. The same concept expressed by another poem entitled Looking at the mountains from the river《上江看山》, where the author describes how the mountains changes the appearance of his journey as his boat runs along the river.

This concept is indicated by the idiomatic phrase “bubu youjing” 步步有景, that is that the landscape is formed step by step, and not just by standing in front of it. It is the same concept expressed by Guo Xi when he says “Its shape [of the mountain] changes with each step”. In these terms, the landscape can only be seen through movement, that is, by walking through it, inside and outside, as with each step a change is created in the observer’s mind through an accumulation of images. This observation methodology is particularly suitable for mountain scenarios, where rocks, trees and rocky masses cover the view of what is behind them. However, if you are in a larger space, for instance lakes, large rivers or plains, the methodology of observation and representation will be different. In this case it is the spatial vastness that makes it impossible to embrace everything with a single glance, therefore the only way is to collect different spatial portions and join them together to fully represent the subject. The same way of viewing and applying on painting can be used to represent areas very distant from each other, through a process of omission. In this sense, it is possible to take a nearby environmental portion and, through a “space jump”, place it alongside a very distant one, omitting everything in between.

Through these two visual methodologies we go against a large amount of material since the natural world is extremely rich and varied, but not all its elements are necessary for the artistic realization of a work. This is also because the presence of excessive quantities of subjects would make the painting confusing and unpleasant, which would make it impossible to communicate the spirit of the natural environment the painter intends to portray to the observer. For this reason, those who observe the subject must make a selection of the necessary and aesthetically relevant elements, following the principle expressed in the last two verses of the poem Plum blossom 《 梅花》 by Li Fangying 李方膺 (1695-1755) which quote: “the eyes they see countless flowers, but only two or three branches are really pleasant “,”触目横斜千万朵,赏心只有两三枝”. In this case the author refers to the plum branches, which when they bloom are loaded with flowers, but only a few follow our aesthetic taste and therefore it is worth painting. Another aspect is that expressed by the phrase “a thousand mountains can be painted, but only one has a green top”, “千山多入画, 只取一青峰”, that is to say that if we paint a large amount of mountains or other subjects, not all of them must be represented in a rich and detailed way so that all attract the observer’s attention in the same way, but only one, or some, depending on the needs of the work, must be richly depicted, otherwise the work becomes heavy and draining for those who are preparing to observe it, depriving them of the pleasure of an aesthetic experience.

Another method of observation of the natural environment, and in particular the mountainous ones, is what is called “observing the big through the small” “以大观小”, formalized by Shen Kuo 沈括 (1031-1095), in his Brush Talks from a Dream Brook《梦溪笔谈》, where he suggests that a mountain scenario can only be understood if viewed from above and from afar, that is, by climbing a hill, inside or outside the area, so that it is possible to embrace it by observing the whole environment that we propose to observe or paint. In this way we will be able to understand its structure and development methods, which would be impossible if we were immersed in its vegetation, rocks or at the foot of some mountain. This concept is also expressed by Guo Xi when he says: “Mountains and rivers are large objects. The people who look at mountains and rivers should look at them from a distance, in this way is possible to grasp the form, the spirit, image and position of the mountains and rivers “,” 山水大物也,人之看者须远而观之, 方见得一障山川之形势气象”. Nevertheless, this concept was already formulized by Zong Bing when he says: “Kunlun Mountain is big and the eyes are small, if it’s too close to our eyes, we can’t see its shape, If it is a few miles away, it will be easy to contain for the eyes”, “且夫崑崙山之大 ,瞳子之小,迫目以寸,则其形莫睹,迥以数里,则可围于寸眸”, in this passage the author suggests the necessity of having a distance view of the subject. The one from a distance is a rather wide and often a quite static view, in fact our eyes embrace a very large area, so even if we move the scenario that stretches in our sight, it would change little, for this reason this view must be compensated with what we previously learned. When we move inside or climb to the very top of a hill, we can then use it as a lookout. In this case the elements we observe are many, but also distant and small, so we will not be able to perceive a whole series of details, and all those minute elements that need proximity to be perceived, such as the texture of the rocks, the branches, trees and leaves, the human presence in the distance or any other subject. A factor that is compensated by observing these elements closely, and then integrated with the distant view.

Similarly, looking closely at trees or rocks lead us to assimilate information on how the natural environment in which they are immersed develops. This method of observation is called “looking at the big through the small”, “以小观大”. A final element that confirms the absence of a unifocal perspective in mountain and water paintings are given to those subjects where the modes of representation have strong perspective characteristics, such as certain types of stones, rocks and buildings in particular. In fact, we see how in mountain and water paintings, buildings can follow different perspectives in the same portion of space, which are then combined in order to meet the artistic needs of the artist and do not in any way respect the laws of a static subjective vision.

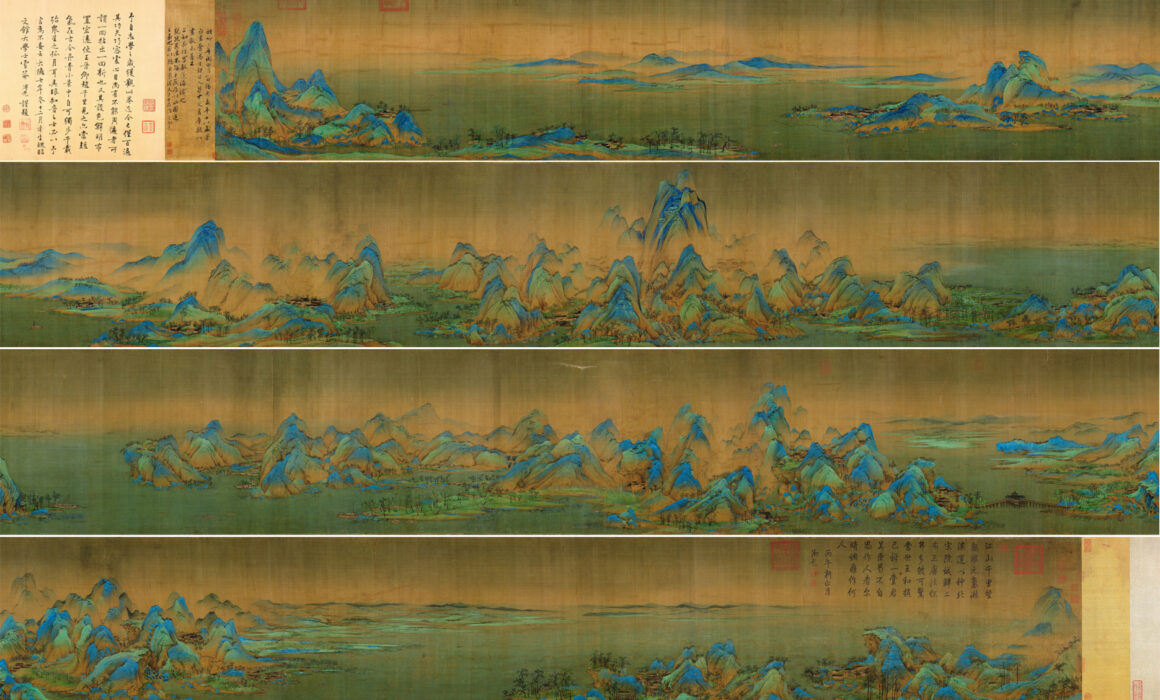

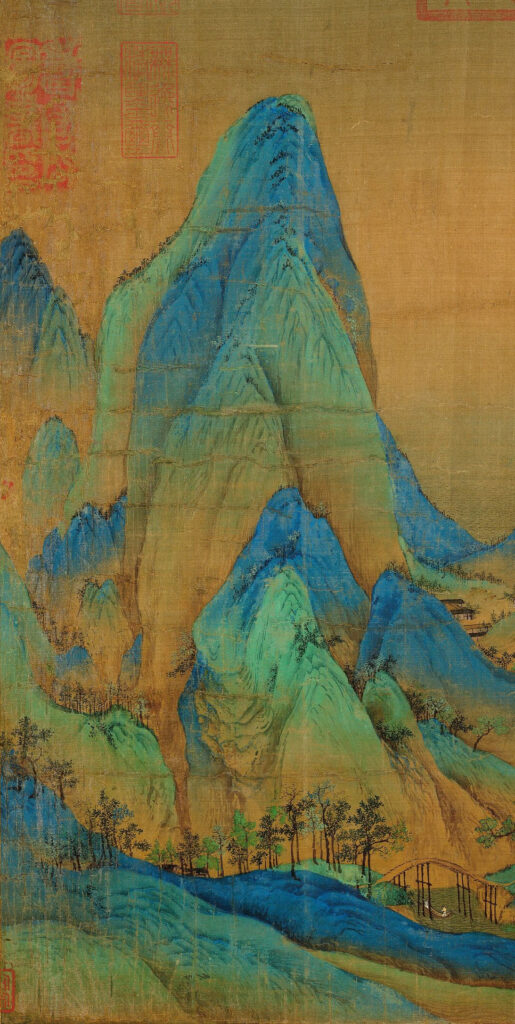

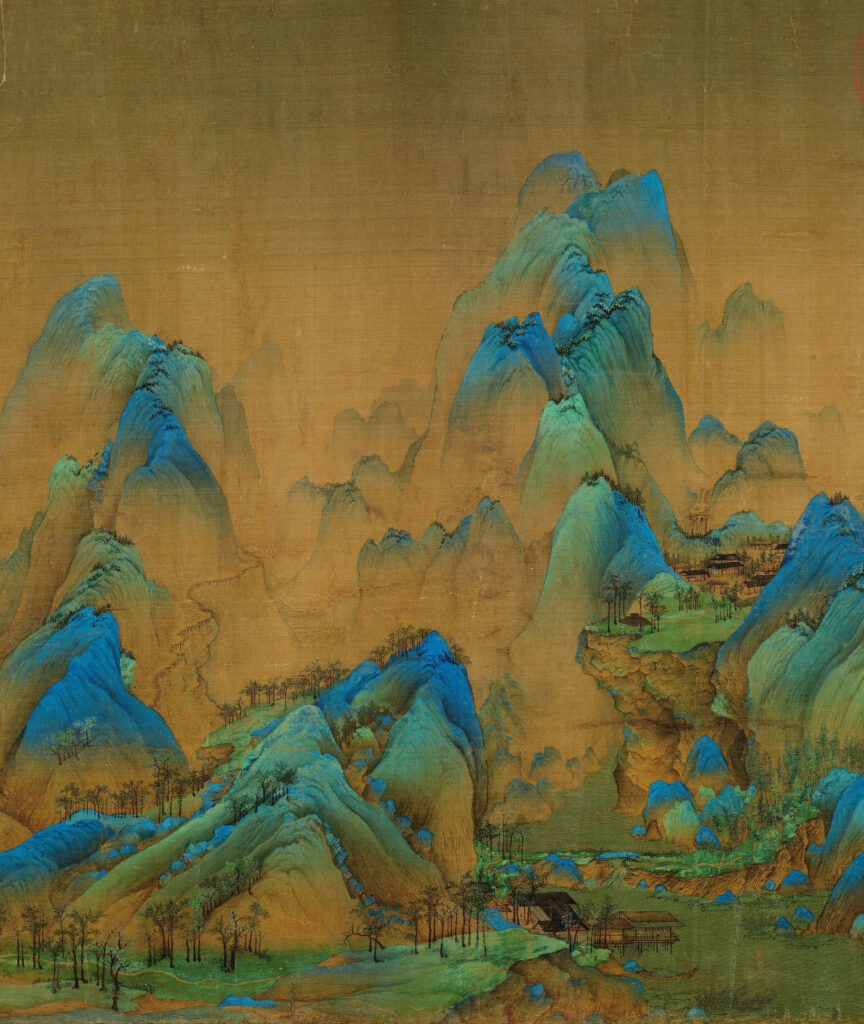

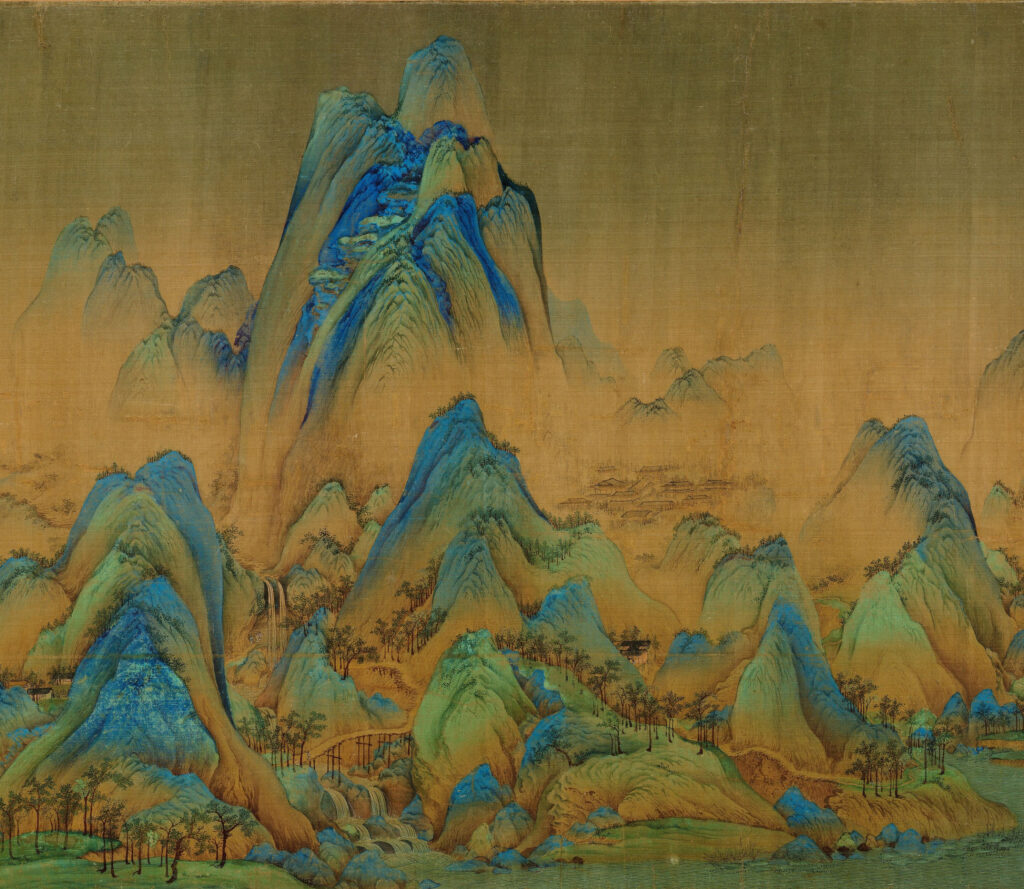

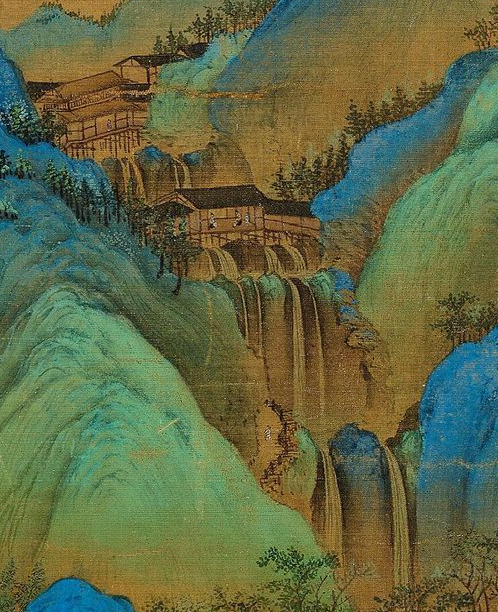

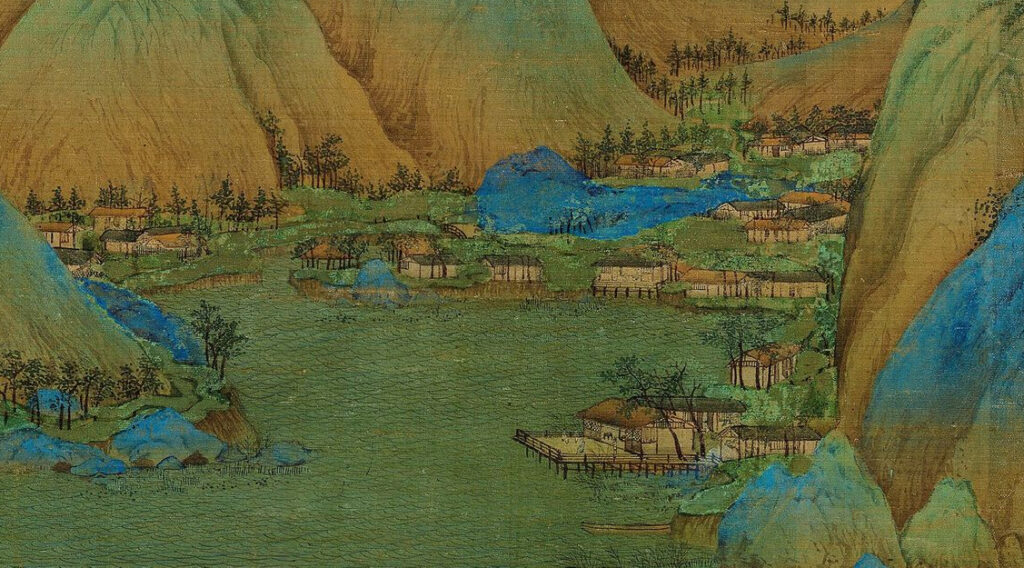

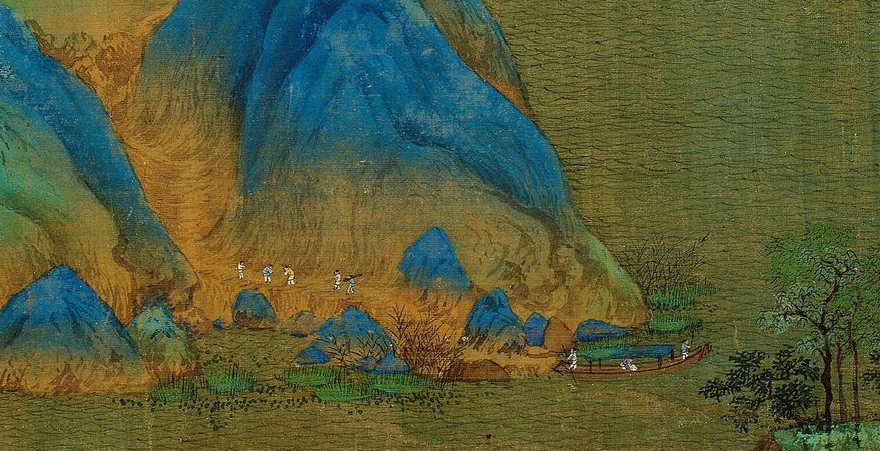

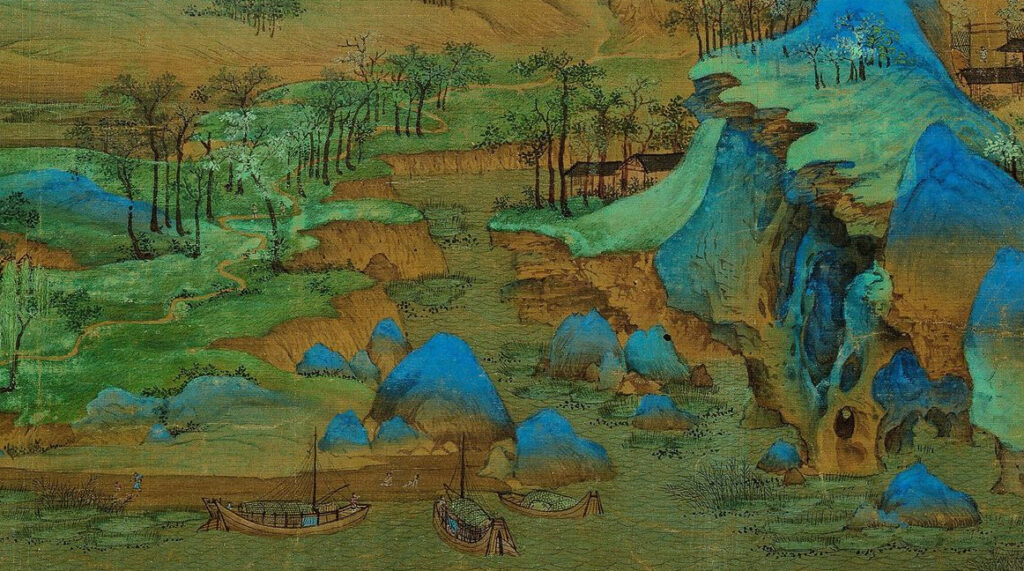

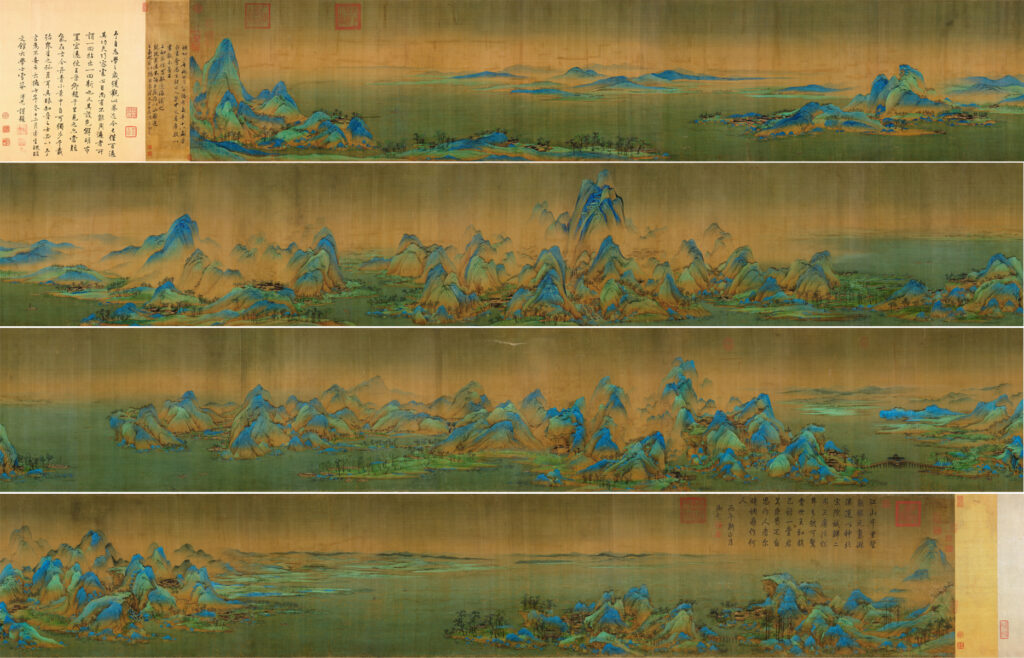

The various ways of viewing the natural environment and the rules of the six distances are often all used simultaneously in the same painting. All of these methods combined, enable the artist to better represent the complexity of the natural scenery. For instance, let’s take one of the most famous works in the history of mountain and water painting, by Wang Ximeng (王希孟, 1096–1119). He was one of the most renowned court painters of the Northern Song dynasty, who painted a 51.5 cm and 11.9 meters long scroll titled A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains 《千里江山图》. This work was made on silk, revealing the lake and river scenery of the mountain complex of Mount Lu 庐山, in Jiangxi province. The mountains are signified by the use of green and blue. Misty and vast, the scenery ever-changing and magnificent. On the mountain, there are high cliffs and waterfalls, winding and quiet, red flowers, green willows, long pines and bamboo trees. In addition to the beauty and executive finesse, the painting also has an enormous narrative charge, describing a cross-section of a twelfth-century rural life in China. In order to represent the richness of the area developed around Mount Lu, the artist uses all of the perspective and visual expedients that we have just illustrated. The great mountains are represented through height distance, the valleys and rivers that extend into the deep are represented through deep distance and the low mountains and hills that develop in the distance through level distance. The river is particularly suited to the three distances rule of Han Zhou, we find distant mountains behind a large stretch of water in the broad distance, and the inaccessible scenarios of the remote distance and the mysterious and dreamlike ones of the shrouded distance. The artist certainly had crossed the area to be able to understand its development and training. He had observed it from a distance to understand its structure, which as Su Dongpo reminds us in the last two verses of the poem On the walls of Xilin: “I can’t see the real aspect of Mount Lu, since I am between its mountains “,”不识庐山真面目,只缘身在此山中”, referring to the concept of “looking at the big through the small”. Wang Ximeng observed the area of Mount Lu closely to grasp its details, it accompanies us in a microcosm rich in life, catapulting us into the rural society of central-eastern China 800 years ago. The painting is animated by about 360 characters, whose size does not exceed half a centimeter.

Many of them are fishermen or travelers on foot who travel on the many roads of the vast plains and mountains, the same path that Wang Ximeng himself travelled. We can see inns, bridges, places of worship and around a hundred boats used for travelling.

We can also see almost 30 villages hidden in the mountains and by the river. The buildings are represented following different perspective rules, which adapt to the general harmony of the composition. The painting also displays the importance of fishing in the society during that time. In addition to the numerous fishermen on boats and along the shore with the rod, we can also see trabuccos and fish farms near the fishing villages. There are also several places of leisure with cultural activities, such as study centres and pavilions on top of the promontories where it would’ve been possible to admire the mountain and river landscape, creating a sort of meta-landscape. We see how the richness and complexity of the work is closely linked to the way in which the environment is observed. Such a painting would be impossible to create using the unifocal perspective or simply observing the area from a single point of view, it would involve a profound knowledge of a vast area through different methods of observation and consequently of representation.

Certainly, a single static point of view is not the means to represent nature and its complexity. Therefore, since the earliest times Chinese artists have endeavoured to find techniques to visually represent the variety and depth of their subject. When the eye of the observer settles on a work composed following these canons, the visual experience will not remain static, because a centre of attraction such as that of the focal perspective will not be present and it would be impossible to observe the whole work without movement, thus cancelling the instantaneousness of the visual experience. This movement will lead him to interact with the work and to feel part of it and not as an external observer. This is precisely because the painter did not interact with the environment as if it were external to it, but lived through it. Many famous painters spent part of their life in the mountains, such as Jing Hao 荆浩 (850-911) in the area of Mount Taihang 太行山 where it was said that he painted tens of thousands of pine trees, or Fan Kuan 范宽 (950-1032) at Mount Zhongnan 终南山, in order to know its secrets and learn to paint natural elements. This attitude of appreciation of the wild natural environment is at the basis of the great development of the mountain and water painting, an attitude that did not exist in the West at least until modern times. But in China, there was the will to know and understand these kinds of environments that inspired wonder and mystery since ancient times. This can be proven in the compilation of texts such as the Classic of the mountains and seas 《山海经》, probably composed in the fourth century BCE, a text that encompasses geographical, mythological, medical notions related to mountainous areas, seas and wild areas inside and outside of Chinese territory. The same appreciation for wild nature is found in sentences pronounced by Gu Kaizhi 顾恺之, a famous painter of the fourth century, who was amongst one of the first to apply himself to the mountain and water painting, referring to the beauty of a mountain area: “thousands of rocks compete for beauty , thousands of valleys compete for flow “,”千岩竞秀,万壑争流 “. So, this appreciation of the mountains, which we have found since the most remote periods of Chinese culture, has led them to admire the mountain environments and not to fear them, as happened for most of the development of western culture, especially towards the Alps. At this point, it would be necessary to write a whole new chapter about the relationship between nature and man in the West and in China; it will be treated elsewhere.

For these reasons it is not suitable to use the term landscape when referring to the mountain and water painting, the term landscape in the mentality and in western languages, brings with it a whole series of elements, which has only been partially treated, ranging to come into conflict with the relationship Chinese artists have with nature and how to express it pictorially. The absence of the use of the mono focal perspective frees the work from the yoke of anthropocentrism, which severely limits the perception of nature as an extremely vast and complex entity, which cannot be reduced to the mere perceptual rules centred around the artist ego. This problem soon appeared to Chinese artists and theorists of painting, which led to a long and rich reflection that implicitly questioned the limits of sight and how to overcome them, often by bending the visual laws to artistic needs, in order to be able to express pictorial subjects as complex as the natural environment. In conclusion, it should be remembered that in the theory of Chinese painting, representing what you see as you saw it has never been the artist’s goal. Indeed this practice was always highly criticized in the texts concerning painting, a famous verse by Su Dongpo quotes: “who discussed painting in terms of form likeness, has the understanding of a child”, “论画以形似,见与儿童邻”, since all the things are characterized by form (external appearance) and spirit, as Jing Hao in the Notes on Brushwork《笔法记》said: “the form without the spirit is a dead form”, “凡气传于华,遗以象,象之死也”.

Look at the painting in high definition

Read the article from the magazine, download it from here

Author: Giacomo Bruni